|

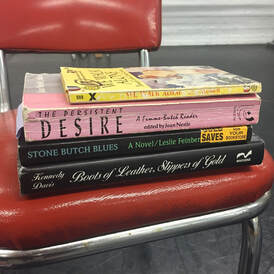

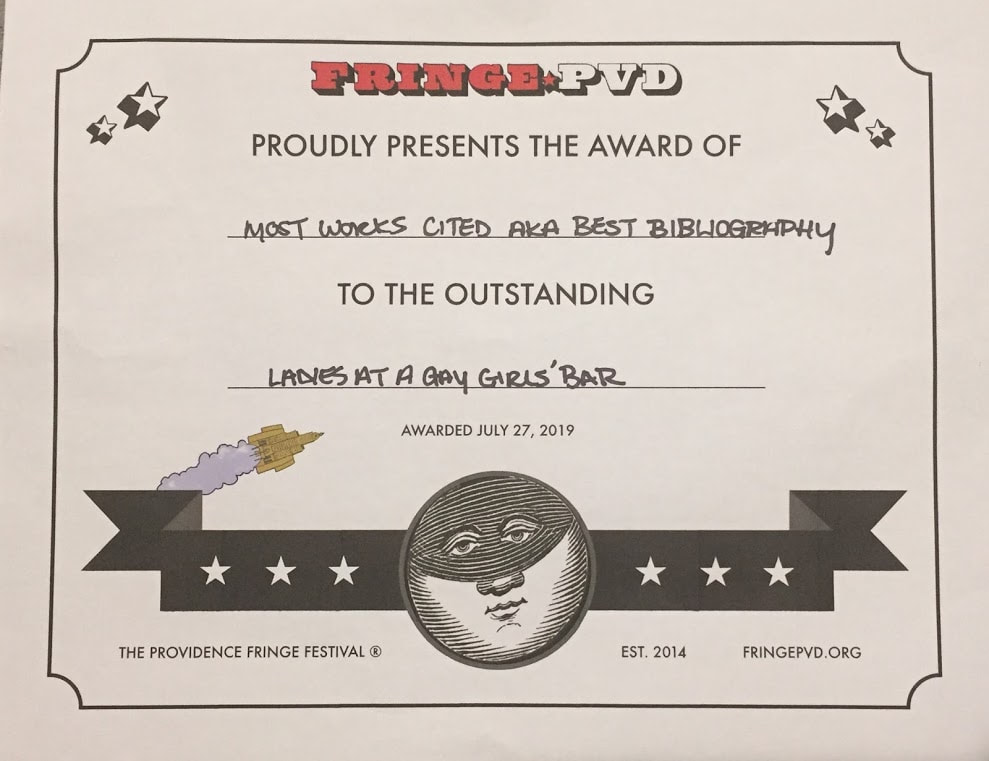

I’ve been lining up social media posts about the books featured in “Ladies at a Gay Girls’ Bar, 1938-1969” and, not surprisingly, find that I have more to say about one in particular than will fit in a tweet, or even an instagram caption. I have some feelings about Stone Butch Blues; about its impact on my tiny slice of the community I came out into, and ultimately about why a butch story dominated our conversations and images of ourselves. The real issue, of course, isn’t with this one book, but with why and how it shaped my tiny slice of my queer generation. Stone Butch Blues is the only book on stage that I don’t directly quote from during the show. I mostly use it as a foil, asking “why are all the femmes in this book like Betty Crocker, Marilyn Monroe, and Florence Nightingale rolled into one?” It’s not the most generous interpretation of the book, but I stand by it. More generously, let’s hear from NYTimes contributing opinion writer Kaitlyn Greenidge, who declared it “the best book for 2018.” In the novel, Feinberg’s avatar, the protagonist, Jess, grows up in working-class Buffalo in the 1950s, at first identifying as a butch lesbian, then realizing she must transition to a closeted trans man as the political debates around feminism, political lesbianism and the very real pressure of finding a job intensify. The story follows Jess’s attempts to organize while doing factory work; it explores upstate New York’s lesbian scene; and it shows the police and state violence she experiences. Along the way, Jess tries to answer questions that I see and hear people around me grapple with today: How do you effectively organize across racial lines? How do you address the generational divides in your community? How do you fight sexism in your workplace, knowing you’re going to have to eat with your foes and band with them later for fair working conditions? The quarter-century-old work does something that most political writing cannot do, something that speaks to our current moment. It reminds us of the psychological and emotional toll of oppression. That “psychological and emotional toll” is surely a huge part of why we as queer youth connected to the book. As different as our experiences might have been from Jess’s, we latched on to that. In the show, I describe a friend loaning me a copy of a book “everyone we know is reading.” This was around 1999 or 2000, 6 or 7 years after it was first published. “Everyone” refers to my cohort of LGBTQIA+ friends from around New England (and the internet) - GSA leaders, poets, theater kids; mostly rural and suburban, mostly white; privileged or brave or stupid enough (maybe all three) to be out in some way, shape, or form. We had, as I say in the show, a lot of words we used for ourselves. We had our identities and we had each other. We met in person for open mics, meetings, and dances, and stayed connected in between via long emails, letters, and zines. The LGBTQ young adult fiction boom was years away. It wasn’t easy to access queer books, or any other media representation, so anything we got our hands on had an outsized influence. On the occasion of Feinberg’s death in 2014, June Thomas wrote: Before the novel Stone Butch Blues appeared in 1993...butch and femme were usually treated as outmoded holdovers...Stone Butch Blues changed that by telling the story of an unapologetically political butch/passing/trans character and by blowing apart stereotypical ideas about role-based romantic relationships. The fierce, “finally, I’m not alone” way that some readers connected with the novel was striking. On the rare occasions when people have unironically handed me a book and declared that it changed, or perhaps even saved, their life, it has almost always been a dog-eared copy of Stone Butch Blues. I’m not sure if the person who first handed me the book said that in so many words, but I know It’s hard to overstate the impact it had on my very specific community of young people and how we positioned ourselves in relationship to the book. It’s a book that will make you depressed, make you cry, make you want to storm whatever real or metaphorical barricades you have in your life. It has a visceral truth to it that stays with you. Following in the footsteps of Stone Butch Blues, we yearned to fight, to matter, to be in community like the characters in the book did. We centered and idolized queer masculinity. With all due love and respect for Stone Butch Blues, for Leslie Feinberg and hir work, hir femme characters are tropes, selflessly nurturing young butches and cooking vegetables in butter just the way their butches like them. I don’t want to give my teenage self too much credit, but I think she may have recognized how cloying those characters are, even as she also wanted to be them. (Especially in the sex scenes, which are not erotica-level explicit but made my virgin self swoon with desire.) I was captivated by the genuine sexual and emotional exchange between butches and femmes, how by healing each others’ pain of gender dissonance and truly seeing each other we can inhabit our authentic selves more deeply. I longed for that kind of connection with someone. I also longed to see myself reflected the way my friends saw themselves in Stone Butch Blues: a strong character, written from autobiographical experience, living a whole and flawed and authentic life. That was missing in my little queer youth community - the possibility of seeing my gender as valid, as queer, as real. My criticism isn’t really with the book. The word is right there in the title - the hero in Stone Butch Blues is the butch, and the hero’s journey is one of self acceptance, struggle for justice, and of gender identity and gender transition. My real issue is why this was the book - why was my group of peers so fixated on a white butch protagonist, why didn’t we also freak out about Zami: A New Spelling of My Name by Audre Lorde, or My Dangerous Desires by Amber Hollibaugh or A Restricted Country by Joan Nestle or Trash by Dorothy Allison or The Gilda Stories by Jewelle Gomez? Racism, misogyny, class, homophobia is the primary answer. In their various intersections, they all color what stories we tell and how we amplify what speaks to us. I want to also ask what did we lose by not having a femme story, or a QPOC story, to imagine ourself in? What could we have gained by having dynamic, complicated, flawed, resilient POC and femme characters in the stories our community most treasures? If you haven’t read Stone Butch Blues, you have no excuse - go read it, absolutely. It’s available for free as a PDF on hir website. And then go read a book by and about femmes.

2 Comments

A Restricted Country by Joan Nestle changed my life when it came out in 1987, six years before Stone Butch Blues. For butches, it may have been our first authentic femme-centered view of our sexuality and our lives. Lesbian literature had been waiting for this perspective too long - and for me, it demanded a change in my behavior and my views of the women I loved. It didn't hurt that Nestle wrote (and writes) from a powerful working class, lefty consciousness.

Reply

Gabriel

5/16/2021 12:06:12 pm

With all due respect, butch masculinity is not the same as straight male masculinity. It is punished as all gender nonconformity is punished. Butches do not oppress femmes in the way that straight men do. Butches are not "men lite." They are punished uniquely for their nonconformity, and I think that's why so many people latched on to this story as a beacon of representation of the varied butch experience. I agree with you on the aspect of racism, though, as it is a white person's story and is not more deserving of the spotlight than stories about queer POC are. My one gripe was of presenting butch identity as a form of privilege, which it is not, in the lesbian community or outside of it.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed